RSoC 2022: Revirt-U - Part 1

By Enygmator on

Hey there everyone! I’m Enygmator and I’m here with the first technical post on the implementation of Revirt-U as part of RSoC 2022!

Outline

- Prologue (what to expect)

- Revirt-U (Type-2 hypervisor for Redox OS)

- A quick intro

- RSoC Implementation Plan (4 steps)

- Implementation (Details)

- Architecture of Revirt-U (how various components of Revirt-U are put together)

- brief overview

- The API (exposed to VMM in order to control VMX)

- VM Memory management (memory+paging in VM & VMM in full detail)

- vCPU implementation (with threads) and

VMEXITfault handling - other details (security, etc.)

- Revirter (The custom VMM for Redox OS that will use the Revirt-U backend)

- Architecture of Revirt-U (how various components of Revirt-U are put together)

- Referenced hypervisors (that served as architectural inspiration for Revirt)

- Epilogue

- Learning OS Dev, and contributing to Redox OS

- Until Later!

Prologue

As you already know from my previous post - “Revirt - Virtualization on Redox OS” - which explains the conception of Virtualization in Redox OS, I am one of the RSoC (Redox Summer of Code) students this year (2022).

So as part of RSoC 2022, I have been working on introducing Hardware-Assisted, Hardware-level virtualization on Redox OS. This feature/technology is called Revirt. More specifically, I’m focusing on the implementation of Revirt-U, which is the type-2 hypervisor of Redox OS and is the “phase-1” of Revirt project plan, and potential integration of Revirt-U into QEMU (similar to how KVM is integrated into QEMU).

Please note that this blog post is purely technical and is about the implementation of the aforementioned features. If you want more details regarding what Revirt-U is and have questions regarding Virtualization on Redox OS (Revirt), refer to this post - “Revirt - Virtualization on Redox OS”, which explains these concepts better.

This post starts with definitions and technological explanations. Then it lays out a plan for Revirt-U (Phase 1). And finally, it gets really technical regarding the ‘architecture + design’ of the ongoing implementation that I’m undertaking, along with reasons for taking those technical decisions.

It’s a little like documentation, a little like a technical report and most assuredly very exciting!

Updates

If I make any updates to this post (which is sometimes helpful for people reading it in the future), I shall make note of it here and st the same time, scratch out older content and replace it with something like “UPDATE1: …”.

Revirt-U

A Quick Intro

Revirt (short for REdox os - VIRTualization technology) is a technology/feature on Redox OS that will provide Redox OS with support for “Hardware-assisted hardware-level virtualization”. It will help us achieve many goals - one of which is to run VMs in QEMU faster.

Revirt-U (revirt_u) is a Type-2 hypervisor “backend”. A Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM), also known as a hypervisor, will be a userspace application that uses ‘Revirt-U’ (a kernel component) as a backend, in order to perform activities like creation and management of Virtual Machines (VMs).

The VMM in this case is classified as a type-2 hypervisor/VMM, since the VMM will be a userspace application that runs on TOP of the OS, and uses an OS kernel component (Revirt-U) as a middle layer (middleware) to use hardware-accelerated virtualization (Intel VT-x, VT-d).

The kernel schedules the user threads. It is on these user threads that the VM runs the guest OS’s virtual CPUs. Revirt-U enables any application to function as a VMM, where the VMM create a VM in its own process address space and control it. There can by multiple VMMs on a Type 2 hypervisor (each in their own process), and each VMM can run multiple VMs, each VM with it’s own OS. The VMM can register handlers for many of the controls, but the kernel retains power of handling stuff that can compromise the OS (and need to run as supervisor), which includes the switching to vmx mode, handling EPT, creating basic VM fault handlers, etc.

Again, note that Revirt-U is not a VMM on its own, rather it is the in-kernel backend component to a VMM in Redox userspace. QEMU can be a VMM which can use revirt_u’s HAV API to run hardware VMs, along with the plethora of functionality it (QEMU) offers when it comes to emulation.

A simple overview of Revirt-U architecture:

RSoC Implementation Plan

The complete project plan is outlined in the post - “Revirt - Virtualization on Redox OS”. As part of RSoC, I’m focused on getting Phase-1 to work (as much as possible). Than primarily includes:

- create the

revirt_ukernel component - create

revirt_uHAV API - Create Revirter, a VMM (hypervisor) that uses

revirt_uHAV API - Provide basic QEMU (VMM) support for Revirt-U

Implementation

While deciding on the architecture and design of Revirt-U, I went through the architectural overviews of various other alternatives, including Hyper-V, KVM, Xen, bhyve, AkarOS etc. Based on some previous discussions on Redox OS Mattermost chat, it seemed like AkarOS’s implementation of the type-2 hypervisor was amazing in terms of simplicity in usage and development, efficiency using para-virtualizability and handled virtualization in a much better way than KVM. You may refer to The AkarOS VMM presentation + explanation (PDF).

So, my initial idea was to implement a very similar model in Redox OS. But I soon realized that the virtual address space model would probably have to be changed significantly to allow for the same type of implementation as that of AkarOS. So, I instead carefully took into consideration the intricacies of how Redox used it’s virtual address space, AND how AkarOS benefited from doing things the way it did, and after lots of deliberation, came upon the following solution that seems to encompass most of the advantages of the AkarOS model, while also keeping the existing Redox userspace implementation the same.

Redox OS mattermost chat user “a4ldo2” (who is also the other RSoC 2022 student) was generous enough to lend a helping hand owing to his familiarity of Redox OS internals, in figuring out ways to handle the EPT paging, memory address space, and related security issues.

The architecture of Revirt-U

A brief explanation

Before I go into the “how” and the “why” of the implementation, I’d like to describe it in a few words.

- Revirt-U will be implemented as a kernel component.

- Any application in Redox OS’s userspace has the capability to become a VMM, where it will be able to use an API (library wrapper around system calls), to create and manage a VM.

- The application (henceforth referred to as the VMM) instructs the kernel to create a Virtual Machine (VM), and map the VM guest’s physical address space into the address space of the VMM (Host Virtual Address space).

- The VMM then spawns threads, each of which will act as a virtual CPU (vCPU) for the VM. The threads and can switch between the VMM code and the VM code.

VMEXITs are generally handled within Revirt-U in the kernel, or in the VMM code.

The API

If an application (VMM) wants to start a VM, it has to be able to contact the kernel. Rather than use a new system call, currently we’re exposing a scheme called revirt: (like open(revirt/custom1/status) can be used). You can read more about Redox OS schemes here. But handling a scheme can be difficult at times, and so a revirt_u wrapper is being used around the revirt_u API, and this wrapper library can be used by a VMM to contact the kernel (like revirt::vm("custom1").status can be used).

For now, the implementation is focused on Intel VT (VMX). When the VMM initiates the scheme, the kernel turns on VMX mode. The VMM then has to simply assign a name and ask Revirt-U (the backend component in the kernel) to create the necessary resources (like the VMCS structure). But one of the most important things that happens next is the mapping of the physical address space of the VM.

VM Memory management

Now, paging is known to be implemented using page tables, that map the host virtual address space (HVA), in which a userspace application resides, to the Host physical address space (HPA). When we’re using a guest VM, we have paging within the guest, where the guest OS’s applications run in the Guest virtual address space (GVA) which is mapped using the guest OS’s pagetables to the Guest physical address space (GPA). Since, the Guest OS in the VM works pretty much like an “application on the Host OS”, GPA is considered to behave the same as HVA.

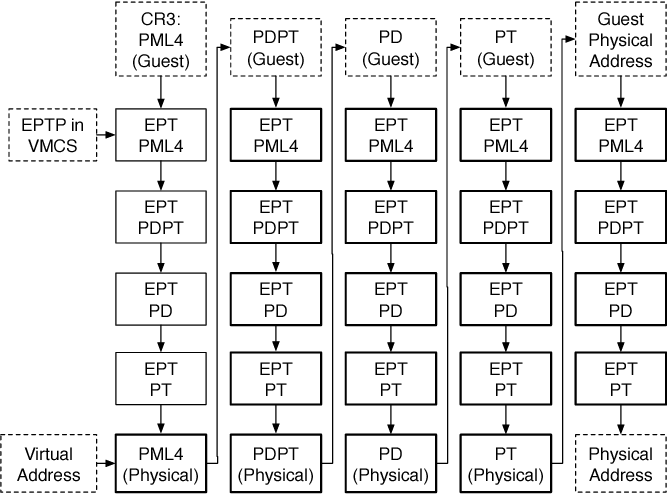

Now, in order to convert GVA to HPA, we need to use the pagetables of the Host AND that of the guest. Assuming that both the guest and host use 4-level pagetables, and the traversal becomes very long (4 * 4 = 16 levels) as seen in the following image, leading to performance issues.

This was initially solved using ‘shadow pagetables’, which ended up reducing number of levels to 4 (but this was a software hack and was still pretty slow). Intel then introduced a new mechanism called Extended page tables (EPT) that implements the page traversal from guest (GVA) to host (HPA) - all 16 levels - completely in the hardware.

Image Source - rayanfam blog (really good reference; check it out)

As you can see, the EPT is a “replacement” for a regular pagetable. We shall henceforth refer to the “regular page table” (host pagetable that converts HVA to HPA) as kernel page table (KPT). Now, just as the KPT maps HVA to HPA, the EPT maps GPA to HPA.

Practically there is no difference between HVA and GPA, but the reason to have a KPT and a separate EPT is most likely because of the irreconcilable issues in the implementation of hardware traversal within the KPT format.

Why am I mapping the VM’s GPA memory frames, into the VMM’s HVA space? and How am I doing it?

So, just like how we maintain KPTs for apps, we need to maintain an EPT for a VM. But given that to us programmers, the EPT and KPT have the same behaviour and only differ in terms of the format of a pagetable entry…

It is common for hypervisors to traverse the EPT during a page fault in the VM, where there’s a VMEXIT into the kernel, which addresses the page fault.

Now, it is common for many VMMs to emulate devices for the VM. Whenever this consists of memory access from the VM to the emulated device (Memory-mapped IO), we are forced to transfer memory from the guest’s physical address space to the VMM’s host virtual address space. This can be done in two way, but both have issues:

- Message passing (system calls) can be used to transfer data between VM’s memory and the VMM’s memory using. This generally has a huge overhead of copy-paste.

- Shared pages can be used, where a frame in HPA is mapped to the GPA and the same frame is also mapped to the HVA page of the VMM, so that the VMM and VM can communicate. But combining the concept of having a separate page fault handler for the EPT and the fact that the same frame is mapped in the KPT (shared with VMM), we quickly realize the problem - If we have a page fault in EPT (for a shared HPA frame), we not only have to resolve it in the EPT, but most likely, we’ll also have to do it in KPT, which would then have to be separately traversed - double traversal due to shared memory (an overhead).

To address both these issue (multiple traversal and memory sharing) AkarOS used the concept of dual pages, a similar version of which we are implementing:

- The solution is to place both the ‘page table pages’ of the EPT (of the VM) and KPT (of the VMM), next to each other in the memory. Each of them occupies 4kB, so when put together, in the 8Kb, the KPT page occupies the top 4Kb and the EPT page occupies the bottom 4Kb.

- Next, at any given moment, both the VMM’s KPT and the VM’s EPT page tables have the same mapping of addresses in their page table entries, albeit in a different format. So traversing either, will lead to the same HPA frame.

The above two points are well illustrated by an illustration. But that illustration contains many details that are specific to Revirt-U’s implementation of the above mentioned idea (the two points), and it would be better if I first share that first.

Please note that I shall explain the benefits of this implementation after the upcoming illustration.

But feel free to scroll down to the image and look at the above two points in actions, and even read the advantages of doing things this way (the usefulness).

In Redox OS, the virtual address space is 256TB in size (2^47). Redox OS allows userspace processes to do anything with the lower half of that which is 128TB (2^46). We have adopted the following mapping for that 128TB:

- The first 512GB is reserved for the VMM

- Each VM will be allotted a 512GB block (at a 512GB memory aligned boundary)

- The PML4 Entry related to the 512GB block, will have a flag (bit 6) set, indicating that all PML3/2/1 pages under it are dual pages, and must be allocated thus.

- Dual pages have the page tables of the EPT and KPT place next to each other, and the corresponding entries in both map to the same memory frame.

Consequentially:

- each VM will have control of memory of ONE PML4 entry (that maps 512GB) in the VMM’s address space

- max number of VMs possible in VMM process space is 255 (0.5TB for VMM ; 127.5TB for VMs)

- If VMM wants to access the memory of a particular VM, then it simply needs to get the HVA by computing

[HVA_corresponding_to_GPA_0x0_for_VM & (0x7FFFFFFFFF & GPA)], whereHVA_corresponding_to_GPA_0x0_for_VMis provided by the kernel (as illustrated in below image).

Problems with Revirt’s method of implementation:

There will only be one complication in the page walking mechanism - when KPT is updated (in page fault), EPT can also be updated at an OFFSET for all page table entries; EXCEPT for the ONE entry in PML4 because each VM’s 512 GB space mapped by each entry in PML4, will have it’s own PML4-EPT, so multiple EPTs can’t be mapped below KPT (just for PML4), and so the EPT-PML4 for each VM will be stored elsewhere, and the EPT_entry for PML4 will have to be updated by getting it’s actual address (which is simply a single memory access - not much overhead). The EPTs for PML3/2/1 will still be mapped as before (below KPT).

All of the above details are pretty confusing, but the following diagram should make things easier to understand.

You can Zoom into the image for clarity, as it is an SVG! (if it doesn’t work, open it in na new tab)

So, how does doing all of the above actually that help us?

-

Since traversing either the KPT or the EPT pagetables lead us to the same HPA frame, in order to resolve a page fault, we can traverse either of them. So now, we can actually use the SAME page fault handler (of the KPT) to resolve the issue. And once the fault is taken care of using KPT (instead of EPT), it simply needs to sync the changes in page table in KPT, to the page table in EPT - which is simply at an offset of 4096 bytes - courtesy of dual pages. So, the page fault handler needs very little modification, and this solves the issue of double traversal by bringing us back to single traversal.

-

Since we now have the VMM’s KPT’s and the VM’s EPT’s entries leading to the same frame in HPA, we can directly access the memory of the VM FROM the VMM. (this can be seen in the previous illustration).

Some other advantages:

- We don’t give the VMM or even Revirt access to the EPTs and handle page mapping and faults directly in the kernel, using RMM (Redox Memory Manager)

- And despite the above point, the VMM has shared access via mapping to the VM’s GPA frames.

- Using the same page fault handler ensures that Revirt will automatically benefit from on-demand paging the moment it is implemented in RMM in Redox OS.

NOTE: Now that you’ve read all the points, if you’re interested in understanding better, it may help you to go over all the points once again, as you’ve now seen the figure and understood some of it.

CPUs (cores) in the VM and handling faults

The VMM has to correctly program itself in order for this to effectively work.

- The idea is that, for each vCPU (virtual CPU) on each VM, the VMM will have to spawn a new thread.

- Since all threads share the address space of the process, they can simultaneously access the “physical memory” of the guest.

- A thread can switch between executing the code of the VMM code, and the code of the guest in the VM.

Any custom VM fault handler, along with any userspace thread scheduling algorithms are available in the commonly shared address space in the first 512GB, because they are a part of the VMM (which resides in the first 512GB).

When the VM faults, it does a VMEXIT into the kernel. If there’s a VMM-registered scheme handler, it gives control to the VMM, or it handles the fault on it’s own in the appropriate manner (which may fail, leading to termination of the VM)

The accesses of various threads in different modes of operation are limited to regions as shown in the illustration below:

Other Details

- Security: This is something which needs to be looked into more closely (in the near future), as it’s obviously very important for the overall security of Redox OS

- SVM Support: I’m planning to look into SVM later on. The intention is to have code for both VMX and SVM in the kernel (as opposed to conditional compilation), and the check for availability can be done at runtime.

- aarch64 | riscv ?: This won’t be a target (at least for the near future). But it will be possible, as Redox OS has a working branch for this.

Revirter

I’m also creating Revirter, which is a light-weight VMM (that uses revirt_u’s HAV API via the wrapper library I’m creating). It is like a highly stripped down version of QEMU.

Reference Hypervisors

I referred to other implementation of hypervisors and Hardware-Assisted virtualization. I only looked into the architecture and high level API, and learnt methods or ways to do things a certain way, but also learnt what NOT to do and how to construct things better.

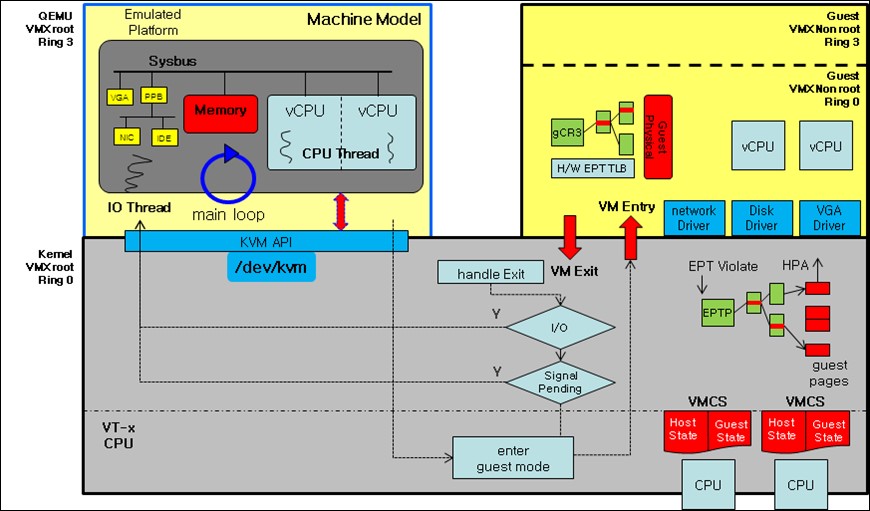

-

KVM: KVM in Linux implements VMs by opening a device on

/dev/kvm. As pointed out by the AkarOS reference PDF, KVM got a lot of things “incorrectly”, as in, things could’ve been built better. A diagram of KVM’s architecture is shown below:

-

bhyve: is a Type 2 hypervisor and is built similar to KVM. I didn’t look much into it’s architecture

I also referred Xen, but it’s architecture has got more to do with Revirt-K, so I’ll be leaving it out of here.

Epilogue

I (and others in the Redox OS community) have various plans and ideas for the future of Revirt and Redox. There were many details not talked about in this post, as they are still being discussed/considered. It still doesn’t mean that I would’ve gotten everything right. There’s guaranteed to be stuff in here that I got wrong. I can only hope to learn from that and amend the errors.

As I implement this feature, I’m getting to learn a lot about the internals of Redox OS, how one can program a VMM (using the Rust language), deciding how the existing system can be changed minimally whilst trying to keep it backward compatible, etc.

Contributing to Redox OS’s future is a lot of fun. I want to thank those who engaged with me in the Redox OS mattermost chat:

a4ldo2- we talked extensively about KPT and EPT paging mechanisms in Revirt-U, security issues, other features to supportbrochard- brought my attention to Xen and it’s relation to Qubes OS, and how Revirt-K could fit injackpot51- helped me figure out Redox OS, coordinate RSoC

Contribute to Redox

In that light, it is clear that contributing to Open source projects has multiple benefits, for you personally, and for the community (the people of this world) at large.

So, if there’s anyone you know, who is looking to dive into the world of creating OSes, you have just 2 steps to do that!

You need to strengthen your knowledge about how OSes work. This has three parts to it:

- By simply reading documentation or code, you won’t be able to make much sense of why something is done a certain way. Instead, you need a comprehensive beginning in a tutorial like manner, so that you feel guided step-by-step.

- Once you start to work the tutorials, you will want to learn more about the stuff being talked about - THAT is when you go to the documentation.

- Then, you can slowly start referring tutorials lesser, and documentation more, as you know you way around things better. This is because docs are structured as knowledge systems, whereas tutorials are structured to be told as stories - which we understand better.

There are lots of places you can find tutorials and docs. I’m listing a small subset here (my recommendations):

Tutorials:

- Brokenthorn Turtorials - best place for a person who just knows

Cand NOTHING else - Philipp Oppermann’s blog OS - best place to start coding OS in Rust (very beginner friendly)

- OSDev website has many tutorials from beginner to advanced

Docs:

- OSDev website documents a LOT of stuff

- Intel developer manual - relatively difficult to read for a beginner

Redox is a great place to start you “advanced OS Dev journey”, as it is NOT a HUGE bloated codebase like the Linux kernel and it is not insignificant either.

Thus making it a good entry point for advanced OS development, and that too, with the Rust language!

I wish you all an awesome OS Dev journey!

Do join our mattermost chat and participate in the development of this OS.

Until later!

If you’ve reached till this point, thank you for reading. I shall be coming back in a few weeks with more exciting updates on Revirt-U!

Until then, keep well.

Bye! 💕💕💕

You can find me on:

- Redox OS - GitLab

- Redox OS - Mattermost chat - username:

enygmator - GitHub

- Encrypted chat on Matrix (like Element chat)